Study areas

A rapid and broad scale multi-criteria site selection process was conducted to identify and rank planning units on their suitability for delivering successful outcomes from NbS28. Two high scoring seascapes were selected as demonstration sites for implementing NbS: Khor Faridah, Abu Dhabi (AD) and Umm Al Quwain lagoon, Umm Al Quwain (UAQ). These sites were the focus of the natural capital assessment conducted in this study.

The AD study site is the coastal lagoon of Khor Faridah in the emirate of Abu Dhabi. The seascape unit is approximately 230 km2. The seascape received a high suitability score for implementation of NbS with potential to deliver triple-win outcomes28. The seascape of Khor Faridah is a complex mosaic of interconnected habitat types and dynamic tidal flows that interact to deliver diverse bundles of ecosystem services. In subtidal water, sandy seabed exists with extensive seagrass beds and hardbottom (limestone) including patch reefs colonized with coral, sponges, and algae. The intertidal is dominated by carbon rich mudflats and extensive mangrove forests including planted mangroves. In the upper intertidal, saltmarsh plant communities exist with other shrubby halophytes occurring on the higher elevation landward supratidal zones.

The UAQ study site is the coastal lagoon of Umm Al Quwain at the heart of the emirate of Umm Al Quwain. The seascape unit is approximately 132 km2. The seascape received the highest suitability score for implementation of NbS with potential to deliver triple-win outcomes28. Similar to AD, The Umm Al Quwain seascape forms a complex mosaic of interconnected habitats shaped by dynamic tidal flows that together support a diverse array of ecosystem services. Subtidal areas comprise sandy seabed interspersed with extensive seagrass meadows and hardbottom substrates (limestone) hosting patch reefs colonized by corals, sponges, and algae. The intertidal zone is characterized by carbon-rich mudflats and extensive mangrove forests, including both natural and planted stands, while the upper intertidal supports saltmarsh vegetation and shrubby halophyte communities extending into the higher-elevation supratidal zone.

Methodological approach and generalized framework for workflow

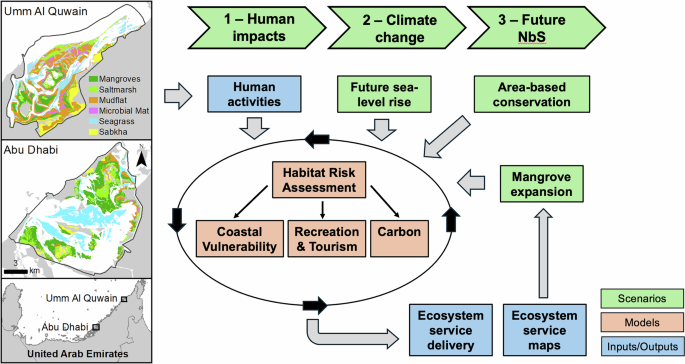

We used a series of models to estimate the impact of different spatial scenarios on blue carbon habitat function and ecosystem service production in terms of coastal protection, tourism, and carbon storage. To address the research questions, we developed scenarios and applied them to this set of models to estimate the impact on ecosystem services from (1) current human activities (baseline scenario), (2) future sea-level rise due to climate change, and (3) future NbS incorporating sea-level rise (Fig. 1). These models are part of the Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST) tool developed by the Natural Capital Project at Stanford University41,42. This suite of open-source software tools help stakeholders explore how changes in ecosystems can lead to changes in the flows of many different benefits to people. We apply InVEST models with best-available data and new data that are most suited to address the challenge of mapping and quantifying the value of ecosystem services relevant to the project objectives and the biophysical characteristics of the sites. The ecosystem services models output ecosystem service supply in biophysical terms which were converted where appropriate to social and/or economic terms for selected services.

The impact on blue carbon habitat function is first estimated using the InVEST Habitat Risk Assessment model (HRA) which does not quantify ecosystem services directly but instead estimates the condition of habitats based on exposure to multiple and cumulative stressors associated with human activities. Since ecosystem services are produced by specific habitat types or groups of habitat types, the condition of these habitats will affect the ecosystem services produced. For this reason, the HRA model was used to forecast change in habitats under climate and NbS scenarios producing maps of functional habitat used as inputs for the ecosystem service models to quantify changes in ecosystem services (coastal protection, tourism, and carbon storage) compared to present and future conditions. To estimate the effects of current human activities on ecosystem services, ecosystem service model results using functional habitat outputs (high, med, low) from HRA were compared to ecosystem service model results assuming all habitats were fully functional. To estimate the effects of sea-level rise on ecosystem services we compared results of the sea-level rise scenario to the present-day scenario. And to estimate the effects of future NbS (mangrove expansion and conservation) we compared results to the sea-level rise scenario. In this way, the impacts of human activities, climate change (SLR), and NbS implementation scenarios on ecosystem services were assessed.

Scenario design

Scenarios play a key role in sharing information, illustrating future options and opportunities, and building consensus for a specific investment or adaptation strategy30. As such, scenario development is integral to the ecosystem service assessment framework. Our primary purpose in applying scenarios was to explore options for NbS that incorporate climate adaptation and quantify co-benefits. Present scenarios for each study area consisted of locally produced coastal habitat maps43 updated for this project using higher resolution data acquired in 2021 for mangroves and other saltmarsh/sparse halophytes44. Then, a future climate change (SLR) scenario was developed which formed the basis for other future scenarios representing NbS actions: mangrove expansion and conservation. The climate change scenario was based on modeling future sea level rise while the NbS scenarios relied more on stakeholder inputs and location preferences.

The IPCC AR6 Report projects that mean global SLR by 2100 will range from 0.38 m (likely range: 0.28–0.55 m) under the SSP1–1.9 scenario to 0.77 m (likely range: 0.63–1.02 m) under the SSP5–8.5 scenario. Based on this, we applied a SLR of 0.5 m to represent a projected value that could occur between 2050 and 2100, depending on the climate change scenario31. While the IPCC AR6 provides global mean projections, the UAE is especially vulnerable to SLR because of its low-lying coastline, extensive coastal development, and concentration of populations in lagoonal and estuarine systems. Given that both AD and UAQ lagoons have large areas of intertidal mangroves and saltmarsh situated within 0–1 m of current sea level, even moderate SLR values (≈0.5 m) pose significant risks of habitat loss, shoreline retreat, and saltwater intrusion that directly affect ecosystem service provision45. For this reason, we selected 0.5 m as a representative value that is both within the IPCC’s projected range and highly relevant to the UAE’s coastal geomorphology and socio-economic context.

Under the 0.5 m sea level rise scenario, mangroves in the lower intertidal drown. Gray mangroves (Avicennia marina) are very sensitive to the duration of inundation due to oxygen demands46. If they cannot build soil elevation to keep pace with rising sea level, they will be lost. This depends on sediment availability and suitable space available for landward shifts. We assume that without protective actions, mangroves will not be allowed to retreat naturally. Similarly, other halophytes in the intertidal such as saltmarshes that are less able than mangroves at building elevation are likely to be lost rapidly due to inundation and erosion47. For UAQ, a bathtub modeling approach was used to estimate future sea level rise of 0.5 m. This was accomplished by designating the 0.5 m contour of the 30 m horizontal resolution CoastalDEM v2.1 for UAE48 as the mean sea level. For AD, a more sophisticated model incorporating atmospheric and tidal forcing was used based on a 0.5 m rise in sea level49. In this case the mean water elevation of the mean water model output was used to represent the future mean sea level. In each case, areas of mangrove and saltmarsh occurring below the future mean sea level were converted to unvegetated mudflats. This scenario assumes coastal areas will be developed in the future with no intervention to allow for or assist a landward migration (natural retreat) resulting in a net loss of mangroves and intertidal saltmarsh compared to present conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition to the mean sea level contour, an average higher high-water contour (i.e., the future upper strandline) was defined 0.55 m above the future 0.5 m mean sea level which is the offset recorded in the local tidal datum50. Public beaches and other places of interest were assumed inundated/compromised and removed when located within 200 m of the future high-water line. Public beaches within both Khor Faridah and Umm Al Quwain lagoons are relatively narrow (typically <100–200 m) and bordered by intertidal flats, mangroves, and coastal infrastructure; as sea level rises and the high-water mark shifts landward, these limited-width beaches are unable to migrate naturally, becoming “compromised” through coastal squeeze and progressive loss of area and function. Roads that intersected the 0.5 m SLR high water line were likewise removed (Supplementary Fig. 1). This scenario provides the basis for the following future NbS scenarios.

The preliminary mangrove expansion scenario was built onto the future sea level rise scenario and assumes that mangroves respond through assisted and unassisted colonization by successfully colonizing all available mudflat and coastal sabkha above the elevation of the future mean sea level. To create the final mangrove expansion scenario presented here (Supplementary Fig. 2a, c), the locations with the top 10% of combined ecosystem service values were used to select priority areas for mangrove expansion from the preliminary mangrove expansion scenario. To value and map areas with the highest provision of ecosystem services, maps of ecosystem service values were standardized and summed into an index to produce combined ecosystem service or ‘Natural Capital’ maps. In addition, higher risk areas (based on exposure to human activities) were given higher values, based on the fact that mangroves are effective at mitigating many types of human impacts51. Furthermore, impacted areas tend to be more accessible, which is a key logistical criterion for mangrove restoration. Only patches with an area >2,000 m2 that overlapped a high scoring planning unit were included. In the final mangrove expansion scenario (Supplementary Fig. 2a, c), these priority areas were safeguarded by conservation actions to protect seedlings and support restoration success. Specifically, off-road vehicles impacts were removed from the mangrove expansion areas and the spatial influence of all other human activities (as implemented in the HRA model) were reduced by 50% as follows: urban development (500 m), dredging (400 m), agriculture (200 m), and vessel traffic (100 m).

The conservation scenarios do not assume any changes in habitat distribution beyond the losses due to future sea-level rise. Rather, these scenarios were implemented through a reduction in human activities and were unique to each study area as described below. In addition, land and sea tour routes and visitor facilities were added (Supplementary Fig. 2b, d)

For AD, the proposed conservation area and regulations were based on a previous stakeholder-led conservation prioritization together with areas with high potential to deliver NbS28,52, and knowledge of human impacts showing the proposed area to have relatively low, and mitigable present threats as depicted in the HRA outputs. Furthermore, much of the area is low elevation and predicted to be submerged with a 0.5 m sea level rise making it unsuitable for urban development. The conservation area encompasses known hotspots for threatened rays as well as Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) habitat. The conservation area regulations mitigate impacts by effectively managing disturbance to seabed or shoreline and destruction of habitat, extraction and damage to marine fauna, and impacts from urban areas within the conservation area. In addition, impact reduction from vessels is achieved by reduced vessel speed and removal of impacts to habitat from off road vehicles is achieved by regulating vehicle access within the conservation area. Specifically, the following human activities were removed from within the conservation area: agriculture, urban development, off-road vehicles, and vessel traffic and associated impacts (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

For UAQ, mitigation implemented in the conservation scenario was based on the draft management plan of the proposed Umm Al Quwain lagoon Marine Protected Area53. This is the only comprehensive up-to-date evidence-based conservation planning scenario that currently exists for the assessment area. These stressor reductions are applied to future habit configuration under 0.5 m sea-level rise though the scenario also includes a new residential development currently in construction on Siniyah Island in the center of the lagoon. The conservation scenario represents the successful application of the proposed regulations for the draft Umm Al Quwain lagoon Marine Protected Area (MPA) management plan (Supplementary Fig. 2d). The scenario, therefore, assumes effective MPA management that achieves the mitigation of specific pressures within each MPA zone and through successful outcomes from the MPA-wide regulations. The conservation scenario mitigates the following current and future pressures to achieve the goals of the draft MPA management plan. Removal of vessel traffic in Zone 1 (Blue Corridor Zone) and Zone 3 (Fisheries Replenishment Zones). Removal of off-road vehicle impacts to coastal habitats (mudflats, saltmarsh, sabkha) within the entire MPA (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Effective management of remaining pressures to reduce the impact buffers by 50% compared with non-conservation scenarios as follows: urban development (500 m), dredging (400 m), agriculture (200 m), and vessel traffic (100 m).

Ecosystem services modeling

Each scenario, represented by modified habitat/land cover maps, was applied first to the InVEST Habitat Risk Assessment (HRA) model to incorporate threats. The outputs from the HRA model were then used as inputs to each specific ES model (except for carbon storage). The following is an overview of each of the InVEST models applied in this assessment with full details of their implementation for each study site.

The InVEST HRA model assesses the cumulative risk posed to habitats by human activities and allows for investigation of consequences for the delivery of ecosystem services42. HRA applies a well-supported exposure-consequence framework to model spatial variation in cumulative risk from multiple human activities across a landscape or seascape. Inputs to the HRA model include habitat maps and spatial data on human activities. Climate change and NbS implementation scenarios were implemented through modification of habitat and stressor data. Outputs from the HRA model include ecosystem risk maps for each scenario where habitats are classified as high, medium, and low risk and are used to estimate the area of functional habitat capable of providing ecosystem services in each scenario54,55. The qualitative risk scores are used to calculate functional habitat capable of providing services using the assumption that higher risk impairs the ability of ecosystems to provide services30. This is calculated by applying the following factors to habitat area under each risk level: low/no risk = 1 (100% functional), medium risk = 0.5 (50% functional), and high risk = 0 (0% functional)30. Thus, functional habitat is not a measure of total habitat area, but rather a measure of the area of habitats able to provide ecosystem functions and services. The model’s results are constrained by input data quality, though a data quality score is used to down-weight uncertain criteria. Outputs should be interpreted relatively rather than across different analyses. The model does not account for historical impacts or indirect stressors, and it assumes risks from multiple stressors are additive. This additive approach may underestimate risk by ignoring synergistic effects or overestimate it by missing antagonistic interactions42.

The HRA models were applied to three abundant habitat types in each study site that provided both the greatest number of ecosystem services and were also feasible targets for NbS interventions. These were mangroves, other halophytes/saltmarsh, and seagrass beds. The risk assessment in the HRA model uses information about all the key components of risk including spatial overlap of stressor and habitat as a measure of exposure along with several other relevant exposure and consequence criteria54. Resilience or recovery potential criteria are consequence criteria based on key life history traits and processes such as regeneration rates and recruitment patterns that influence the ability of habitats or species to recover from disturbance54. These were the same for each study site as shown in Supplementary Table 1. The exposure and consequence criteria (other than resilience criteria specific to each habitat) varied between study sites and are shown in Supplementary Tables 2 & 3. The input layers specific to each study site are described below.

The spatial data layers were updated repeatedly throughout the project to represent the most current spatial patterns of observable stressors up until February 2023. For example, marine construction, dredging and urban development are constantly changing and can be easily observed in satellite imagery. Artificial light at night (light pollution) was evaluated but excluded due to uncertainty on the impact to marine habitat types and insufficient data on the distribution of the horizontal irradiance.

For AD, a total of six human pressures were included as spatial data layers. Pressures are the stresses that human activities place on the environment.

-

Urban development (buildings, roads, building sites, planned development)

-

Agriculture

-

Dredged seabed

-

Vehicle tracks on soft sedimen

-

Marine vessel traffic

-

Vessel impacts to seabed

The HRA model allows the user to set a buffer of a specified distance around a given stressor layer to expand the influence of that stressor beyond the mapped physical footprint. For example, marine vessels generate a zone of influence that extends beyond the physical location of the vessel through noise and wave generation capable of disturbing habitat structure and species behavior. For all scenarios except conservation the following impact buffer distances were applied based on relative spheres of influence estimated using expert knowledge of human impacts: Urban development (1000 m), agriculture (400 m), dredged seabed (800 m), vehicle tracks (0 m), vessel scars (0 m), marine vessel traffic (200 m), and marine construction (800 m). For example, the pollution from noise, artificial lights and chemicals emanating from urban development extend far beyond the structural footprint of urban development. The same set of six human pressures were applied to all present and future scenarios except for the conservation scenarios.

Existing and planned urban development. This layer represents the spatial extent of urban development in Khor Faridah including land with existing urban areas (i.e., built up areas) and areas cleared for development (i.e., disturbed land). The following classes were extracted from the habitat and land-use map developed and provided by the Environment Agency—Abu Dhabi (EAD): ‘High-density urban’ (small area), ‘Low-density urban’, ‘Oil industry’ (single location), ‘Other industry’, ‘Paved roads’, ‘Port areas’, and ‘Disturbed ground’. New urban development/ disturbed ground not included in the existing map was digitized based on recent high resolution Planet Labs imagery and appended to the combined layer.

Agriculture. Agricultural runoff is a source of pollution for natural habitats and may include pesticides, herbicides, and/or fertilizers. This stressor layer was formed by combining classes from the habitat and land use map developed by EAD including ‘Date plantations’, ‘Farmland’, and ‘Livestock areas’.

Dredged seabed. Dredged seabed data was created by updating the dredged area class in the benthic habitat map created by EN-WWF in 201843 with dredged areas clearly visible in very high-resolution satellite images for December 2022.

Vehicle impacts. On coastal flats, motorized vehicles cause physical damage to soft substratum and plants on mudflats at low tide, coastal sabkha and saltmarsh, disturb wildlife and also introduce contaminants from tires and fuel. To map vehicle impacts, we mapped areas with evidence of wheel track marks (motorbikes, quad bikes, 4×4 vehicles) on coastal habitat types visible in very high-resolution satellite imagery (Google Maps).

Vessel traffic. Vessel impacts occur through noise, waves, chemical pollution and the risk of collision with marine megafauna. Vessel pathways and intensity of traffic was mapped using AIS (Automatic Identification System) data obtained from Global Fishing Watch. The data represents the sum of vessel presence hours in each grid cell from January 2019 to January 2022.

Vessel impacts to seabed. This layer represents propeller disturbances to shallow marine habitats. The layer was created by digitizing polygons around impacted areas visible in very high-resolution satellite imagery (Google Maps).

For UAQ, a total of five human pressures were included as spatial data layers. Pressures are the stresses that human activities place on the environment.

-

Urban development (buildings, roads, building sites, planned development

-

Dredged seabed

-

Vehicle tracks on soft sediment

-

Marine vessel traffic including areas inferred from propellor scars on seabed

-

Marine construction (reclaimed land, causeways, created beaches)

For all scenarios except conservation the following impact buffer distances were applied based on relative spheres of influence estimated using expert knowledge of human impacts: Urban development (1000 m); dredged seabed (800 m), vehicle tracks (0 m), marine vessels (200 m), and marine construction (800 m). For example, the pollution from noise, artificial lights and chemicals emanating from urban development extend far beyond the structural footprint of urban development. The same set of five human pressures were applied to all present and future scenarios except for conservation. In addition, a residential development currently in construction on Siniyah Island was included in the urban development layer for all future scenarios including conservation.

Existing and planned urban development. This layer represents the spatial extent of urban development in UAQ. The ‘built-up’ class was extracted from the 2021 WorldCover data (10 m resolution) based on Sentinel-1 and 2 data produced by the European Space Agency. Any erroneous urban areas were removed where they did not correspond with the most recent high resolution Planet Labs imagery. The planned Phase 1 footprint of the Siniyah Island development was digitized from online draft planning documents.

Dredged seabed and marine construction. Dredged seabed data was created by updating the dredged area class in the benthic habitat map created by EN-WWF in 201843 with dredged areas clearly visible in very high-resolution satellite images for August 2022. Similarly, marine construction including recently engineered beaches were updated with reference to very high-resolution satellite imagery.

Vessel and vehicle impacts. Vessel impacts occur through noise, waves, propeller disturbance to the seabed, chemical pollution and the risk of collision with marine megafauna. Vessel pathways and intensity of traffic was mapped using AIS (Automatic Identification System) data obtained from Global Fishing Watch ( The data represent the sum of vessel presence hours in each grid cell from January 2019 to January 2022. The main channels through the lagoon were also included to represent the likely routes of other vessels (i.e., small fishing and recreational vessels) outside of the scope of AIS. These spaces were identified using participatory mapping of local knowledge on the routes used by small boats for fishing. On coastal flats, motorized vehicles cause physical damage to soft substratum and plants on mudflats at low tide, coastal sabkha and saltmarsh, disturb wildlife and also introduce contaminants from tires and fuel. To map vehicle impacts, we mapped areas with evidence of wheel track marks (motorbikes, quad bikes, 4×4 vehicles) on coastal habitat types visible in very high-resolution satellite imagery (50 cm Maxar imagery in Google Maps).

The InVEST Coastal Vulnerability (CV) model estimates exposure to storm induced coastal erosion and flooding. The model produces a qualitative estimate in terms of a vulnerability index, which identifies areas with relatively high exposure to erosion and inundation during storms42. By combining these results with population data, the model can indicate areas along a coastline where humans are most vulnerable to storm waves and surge56. Inputs to the CV model serve as spatial proxies for various complex shoreline processes that affect exposure to erosion and inundation. Storm surge and waves are not modeled in nearshore regions. It also does not account for interactions between different variables. In addition, the model assumes that habitats provide protection to regions regardless of the geomorphic classification. Finally, the computation of wave and wind exposure is highly simplified. The CV model outputs highlight the potential physical protective service offered by coastal habitats and allow for quantification of this service in terms of people and property protected56.

The CV model operates at the shoreline of the study area using a user-defined resolution set to the minimum spacing of 100 m for this application. Key inputs for the CV model were generated by project partners at the International Center for Biosaline Agriculture (ICBA)44 including: (1) a shoreline vector polygon; (2) a geomorphic classification vector line of each 100 m segment of the shoreline, and (3) current and future sea level rise point values.

For each shoreline segment, the model produces a relative hazard index and quantifies the habitat role in coastal protection. Coastal vulnerability is then quantified in terms of length of shoreline and population both protected by habitats or located within high hazard areas. To integrate habitat quality, habitat-specific risk maps output from HRA were used as inputs and coastal protection rankings were scaled to risk values (Supplementary Table 4). The CV model was run separately for each study site though the input layers and parameters were similar for both sites and are described below.

Ten spatial data types were integrated into the InVEST CV model including coastal habitat maps, bathymetry (inshore and offshore), wind model, wave model, fetch distances, point locations for sea level (past and future), human population density, a newly created shoreline vector, coastline geomorphology and erodibility, and land elevation.

Coastal habitat data. Coastal habitats (mangroves, seagrass, saltmarsh and others) play a vital role in reducing the threat of coastal hazards such as storm surges and wave energy that can erode shorelines and impact coastal communities57,58. The highly vegetated habitat types such as mangroves offer the greatest shielding against coastal erosion. For the main habitat types, the model allows a ranking of the habitat types based on their relative capacity to offer a physical protective function. Although seagrass meadows attenuate waves and stabilize sediments in many settings, we assigned a lower protection rating in this study because meadows in both lagoons occur mainly in subtidal areas below mean low water and are dominated by small, low-canopy species (Halodule uninervis, Halophila ovalis, Halophila stipulacea), which provide limited hydrodynamic resistance compared to taller temperate species. The following ranks were applied for low and no risk habitats (as defined by HRA):

-

Habitat Rank 1 – Very high protection/low exposure (mangroves, coral reefs)

-

Habitat Rank 2 – High protection/low exposure (saltmarsh/ halophytes)

-

Habitat Rank 3 – Moderate protection/exposure (coastal sand habitats, oyster beds)

-

Habitat Rank 4 – Low protection/high exposure (subtidal seagrass beds)

Habitat risk. To incorporate the effect of human stressors on habitat’s ability to provide coastal protection, the qualitative risk maps from HRA were used as habitat inputs to CV and the above risk rankings adjusted as shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Bathymetry. A shelf-edge contour was created using the 43 m isobath from data (GeoTiff) downloaded from the General Bathymetric Chart of the Ocean (GEBCO) on a 15 arc-second interval grid. Wave height and power is influenced by water depth. The GEBCO bathymetry was used to represent offshore waters and was merged with a much finer resolution bathymetry provided by EAD.

Wind and wave models. Both wind and wind-generated waves are considered when mapping the Relative Exposure Index59. Historical (1991 to 2020) wind and wave variables (ERA5 data) for the Arabian Gulf were downloaded from the Copernicus Climate Change Service of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts44. The ERA5 wave data provide an hourly time-series for mean wave direction, mean wave period and the significant height of combined wind waves and swell at 0.5 × 0.5 degree resolution. Ten years of data (2011–2020) were used to calculate the Relative Exposure Index (REI)59 required by the CV model. Specifically, the average in each of the 16 equiangular sectors (0 deg, 22.5 deg, etc.) of the wind speeds in the 90th percentile or greater observed near the segment of interest. For the 10 yr wave dataset, the 90th percentile of wave power was calculated by first estimating the wave power for all waves in the record, then splitting these wave power values into the 16 fetch sectors defined above. For each sector, wave power was then calculated by taking the average of the top 10% values. The relative exposure of a shoreline point to waves is estimated by the model as the maximum of the weighted average power of oceanic waves and locally generated wind waves as defined by the maximum fetch distance inside the lagoon.

Maximum fetch distance. The maximum horizontal distance, unobstructed by a landmass, over which wind and wave-generating winds blow, was measured in GIS from the seaward shore of the khor to the northernmost shore of the Arabian Gulf. This distance was approximately 830 km. The maximum fetch distance inside the lagoon (20 km) was also measured to separate the wind driven from the oceanic swell influence on coastal vulnerability.

Sea level variation. Point data generated from multiple models of sea level rise was downloaded from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (ICBA 2023). Three data points were located in the assessment area. The data provide sea level estimates for the years 2000–2050 using the high emission climate scenario (SSP5-8.5). To calculate sea level variation in the study area, the 2000 water level was subtracted from the 2050 water level for each of the three data points.

Human population density. Population density data was acquired from WorldPop (www.worldpop.org) using the United Nations WPP-Adjusted Population Density, v4.11 estimated for ~1 km cells.

Shoreline vector. A new shoreline was created by ICBA44 and subsequently updated to include marine construction taking place in 2022 and 2023. The shoreline was delineated using a multi-sensor combination of Sentinel 2 (10 m) and Landsat 8/9 OLI (30 m) data to classify water, tidal flats and terrestrial land. This was then refined with higher resolution satellite images to refine an existing coastline obtained from OpenStreetMap.

Land elevation. Land elevation above sea level was mapped at 30 m resolution using a digital elevation model (CoastalDEM30 v2.1) acquired from Climate Central. This model has been improved in the coastal zone using ICESat-248 and machine learning methods. The DEM provides a median vertical error for low-lying ( < 5 m) coastal UAE of -0.14 m. Elevation was averaged within a 100 m radius window.

Coastline geomorphology and erodibility. The relative erodibility of the coastline when exposed to waves is dependent on the physical geomorphological properties of the coastline. To map relative coastal erodibility, coastline segments were created by technicians at ICBA and assigned a geomorphological class (5 classes were defined) and a score representing relative erodibility from low erodibility concrete and rock sea walls to high erodibility sand beaches and mud flats44. Segments were classified using very high resolution (50 cm) satellite imagery in Google Earth together with ground validation using Google Street View and physical visits to selected sites.

The following classification was applied:

-

Very low exposure (large sea walls & rocky shores)

-

Low exposure (small sea walls)

-

Moderate (rip-rap, rubble)

-

High (sandstone)

-

Very high (tidal flats, sand beaches and dredged channels)

The InVEST Recreation model quantifies the value of environments by predicting the distribution of person-days of recreation, based on the locations of habitats and other features that influence people’s decisions on where to recreate such as infrastructure, industrial activities, and access. In the absence of empirical data on spatial visitation, the model is parameterized using geotagged photographs posted to the website Flickr™, a proxy for visitation referred to as photo-user-days (PUD)60. The tool estimates the contribution of each attribute to visitation rate for each cell in a user-defined grid using linear regression42. The model predicts how future changes to features will alter visitation rates and generates maps showing current and future patterns of recreational use. Outputs include maps of current patterns of recreational use and maps of future patterns of use under alternate scenarios. In this way, the value of natural habitats can be quantified in terms of the number of people visiting the areas of interest. Estimated number of visitors under each modeled scenario can then be converted into economic terms by applying spending estimates derived from travelers to the UAE.

To increase data available for training, the model was run for the entire UAE and results subset for the study site. The model was run at 1000 m resolution using a hexagonal grid to minimize spatial bias (vs rectangular grid). Flickr data from 2005 to 2017 (the max time range available) was used to generate initial estimates of visitation (based on PUD – Photo-User Days) and to calibrate a linear regression model. The number of visitors per grid cell was calculated by applying a conversion factor based on scaling the sum of PUD across the entire UAE to 2019 national visitation data for the UAE from UN World Tourism Organization sum of ‘Inbound’ and ‘Domestic’ visits (15,982,000) for the purpose of ‘holidays, leisure and recreation’ (https://www.unwto.org/resources-unwto).

To validate the InVEST Visitation model results, separate city visitation estimates (2019 data) for AD and UAQ were obtained from Colliers International61,62,63. We assumed the same proportions of ‘holiday, leisure an recreation’ visits as estimated by the UNWTO data above for international (47.1%) and domestic (48.2%) visitors. To compare with the InVEST results, polygons representing each city limit were derived from Google Maps and GADM and used to select the grid cells from InVEST to calculate the modeled city populations. The validation approach suggested greater accuracy for AD, with the InVEST estimate 3% higher than Colliers. For UAQ, the InVEST total modeled population was 32% lower than the Colliers estimate.

Finally, for each scenario, we used the HRA risk results to calculate the percentage of each hexagonal grid cell represented by mangrove functional habitat. This assumes that healthy (less impacted by humans) mangroves are more attractive to tourists62,63. Tourism in UAE coastal lagoons is dependent on healthy mangrove ecosystems, with activities such as guided boardwalks, birdwatching, kayaking, and educational visits tied to the aesthetic, ecological, and wildlife-rich features of mangrove stands40,64,65. Degradation or loss of these mangroves leads to declines in biodiversity encounters—particularly birds and fish—reducing the appeal of wildlife viewing and nature-based educational programs, while diminishing the visual and experiential quality sought by tourists.

The model predictors are the features associated with natural capital (coastal habitats) and built capital relevant to recreation and tourism (e.g., roads, hotels, restaurants, tourist attractions, activities), areas less appealing to most tourists (industrial sites), and infrastructure that influences access and cost (e.g., distance to major airport, roads). Distance to airports, industrial land use and road networks were based on current infrastructure and applied to all scenarios. Mangroves and beaches were selected as the focal habitat types. Places of interest for visitors were mapped as point locations using OpenStreetMap and included cafes, camp sites, fountains, hotels, monuments, museums, parks, picnic sites, theme parks, tourist info, and viewpoints.

The InVEST Carbon model estimates the amount of carbon stored within a coastal area based on habitat coverage42. Our implementation of this model was informed by recent sampling of carbon densities across habitat types in each study area66. Carbon markets for 2022 range in value from $20-80 USD per metric tonne of carbon. New markets are valuing carbon storage higher when accompanied by verified co-benefits. We chose to use market value of avoided emissions to value carbon stocks and applied a mid-high range value of $50 per metric ton of carbon (The World Bank 2022).

The model was computed using newly acquired field sample data on above and below ground carbon storage collected across multiple habitat types in each study area. At the time of this study the data on carbon sequestration rates was not available. Mangroves contributed most to total carbon storage at the per hectare unit and second only to mudflats when extrapolated to the entire assessment area. Due to uncertainty and lack of knowledge on the effects of human stressors on carbon sequestration and storage, we did not incorporate the HRA results into carbon estimates for any future scenario. For the present scenario, because the input data is based on recent sampling, we assume that measured values reflect the effects of anthropogenic impacts and/or inputs.

The blue carbon assessment measured three main carbon pools: (1) aboveground living biomass (trees, scrub trees, pneumatophores), (2) belowground living biomass (roots), and (3) soil carbon. Sample collection and processing closely aligned with the methods recommended by the Blue Carbon Initiative67. Samples were collected from six major blue carbon habitat types66. To standardize soil carbon for comparative analyses only stored carbon in the top 50 cm of the core was used.

link